DeAndre Ayton is introducing me to three of his best friends. First there’s Josh. Josh’s voice is that of a generic white dude and he makes appearances when DeAndre is forced to do interviews. Josh has one purpose in life: to help the world see how fabulous a guy DeAndre is.

So there’s Josh, and then there’s Eric, whose voice, not surprisingly, is nearly identical to Josh’s. Eric is new and DeAndre is still trying to carve out his character. At the moment, it boils down to a collection of hobbies—like playing NBA2K and Fortnite, lots and lots of Fortnite—which, coincidentally, DeAndre happens to share.

So there’s Josh and Eric. And then there’s Alejandro. Alejandro is DeAndre’s favorite of the trio. He’s been around the longest and appears most frequently. “If I don’t want to do something I have to, I’ll just make fun of it,” Ayton says. Certain questions “bring out Alejandro.” This, Ayton proudly adds, often “shocks” whomever he is speaking to. I ask Ayton if he has an example he can share. He does. Over the past year, he says, Alejandro would often come out if and when Ayton attended a University of Arizona frat party.

“I didn’t want to talk to anyone and so I told everyone my name is Alejandro. I said”—and here Ayton’s voice shifts into a not-so-great impersonation of a Latino accent—“Who’s DeAndre? My name is Alejandro. Where are you getting this DeAndre kid from?”

Ayton’s always had some jokester in him. His mother, Andrea, says she always thought he’d become a comedian. Her point is that these characters have always lived inside him.

But lately Alejandro has been making more appearances. This, of course, is thanks to Ayton’s budding basketball fame. In just a few months, he’ll hear NBA Commissioner Adam Silver call his name during the NBA Draft. Ayton’s name might be the first Silver calls out, or maybe the second. Perhaps it will be the third, but it’s highly unlikely Ayton will have to wait any longer than that, not with his bouncy 7-1, 260-pound frame, Popeye-like muscles and deft feet, which his mother says were honed as a kid dancing to Michael Jackson videos.

It’s a blend of physical tools and skills that make scouts woozy.

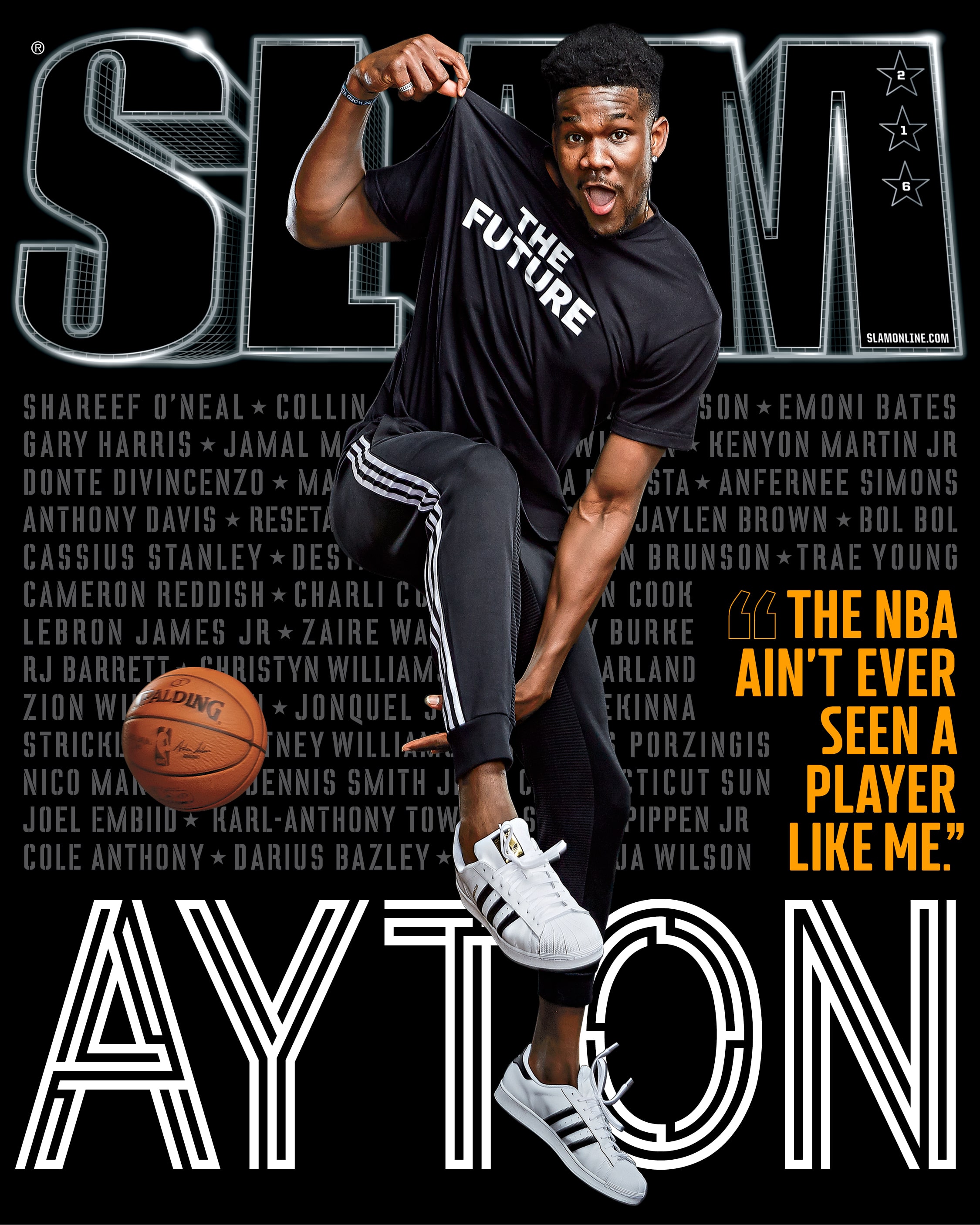

And Ayton knows it. He knows how talented he is, how great he can be. “The NBA ain’t ever seen a player like me,” he says at one point during his afternoon with SLAM. He may be just 19 (he’ll turn 20 in July), but his future, to be the future of the game, is a future he wants and expects. And yet to fulfill all the promise packed into all those muscles, to see that future come to fruition, he’s going to first have to learn how to navigate all the bumpy terrain that comes along for the ride.

It’s early April and we’re in Phoenix, and it’s about 12:30 when a smiling DeAndre Ayton—he’s always smiling, unless you make the mistake of trying to wake him up in the morning—strolls down the ramp leading toward the basketball court where our interview and photo shoot are scheduled. This is notable because our interview is scheduled to begin at 12:30, meaning Ayton is on time, something rarely said about NBA players, meaning Ayton’s either incredibly punctual or doesn’t yet recognize how much of his surrounding world orbits around him. It could be the latter. But the half-dozen times over our few hours together that Kyle Weaver, Ayton’s former high school coach and current personal trainer, has to remind him where he left his wallet and phone and keys doesn’t exactly paint the picture of a perfectly organized teenager.

Ayton spends the afternoon cracking jokes and admiring his own photos—“That’s sexy shit,” he exclaims after seeing one—and swatting away his trainer the first, oh, half-dozen times Weaver attempts, perhaps only half-jokingly, to transform the photo shoot into a practice session. Upon hearing the photographer ask Ayton to dribble for the camera, Weaver, a Phoenix native with dark black hair who’s built like the former college guard he is, strolls over, wearing a grin and carrying a second ball.

“Get that shit away,” Ayton, smiling and relishing a day off, responds. He’s spent hours with Weaver over the past few weeks working on his handle, going through various drills where he pounds both ball balls into the ground. He’s never really needed guard skills before, not when he’s always been the biggest and strongest man on the court, but he knows the NBA game is different today, and that nowadays even seven-footers are asked to shoot from deep and put the ball on the floor.

So he spends his pre-draft days strengthening his ball skills and launching three-pointers and not leaving the floor before draining 50 shots from deep, which, Weaver says, Ayton usually does in 70 or less attempts. The form’s not perfect, but it’s far from clunky. Watch him shoot and then cue up the highlights of him bullying opponents last season during his lone year at Arizona, to the tune of 20.1 points and 11.6 rebounds per game, and you can see why an NBA general manager and an assistant general manager that I spoke with for this story both described Ayton as an “incredible” offensive talent, exactly the type of player a 21st century NBA offense can and should be built around.

“There are a lot of versatile bigs, but I’m a different versatile big,” Ayton says. “The versatile bigs that are in the NBA, all the unicorns, they start outside in. I establish myself down low before I come out. That was just old school to me—that’s how they taught me how to play.”

But also, “You know, I hate being a big man, because I don’t like jump hooks. I don’t want to see a seven-footer do a jump hook so I don’t do them. I’m an entertainer, I like entertainment. I like to entertain myself.”

Which is great. The challenging part is learning how to adjust when the world around you suddenly feels as if it’s closing in and choking the fun out of the fun, or entertaining, aspects of your life.

Ayton wasn’t always a boisterous Joel Embiid clone. Growing up in The Bahamas, he didn’t start playing basketball until the fourth grade and, by his own admission, he was “trash.” But by age 12, he had shot up to 6-5 and so naturally he caught the eye of some coaches who reached out to some scouts who connected with the Aytons and, before long, DeAndre and his family were packing their bags and headed to San Diego and playing alongside kids who had no qualms with reminding him how trash he was.

“They really got on my ass,” Ayton says. He was afraid to talk back. He knew they were right, that his game was raw. But also, “I had a little accent back then and a deep voice and they would make fun of it.” He adds that he had a bit of a stutter.

Driven at least partially by that ridicule, he began spending school nights in the gym, sometimes until 2 a.m. His skills grew. So did his body. “I got pretty good at basketball pretty fast,” he says. He was dubbed the best eighth-grade basketball player in the country. With that came confidence, on the court but also in personality.

“As I got better I started disrespecting [the people I was playing against],” Ayton says. He’d run with older pros trying to get into the NBA and drop lines like, Yo, you play in the G-League—what? Man, I’m going to the NBA, and, How old are you? You already lived your life. I’m going up and you’re going down.

It was quite the transformation.

During the initial years in San Diego, Ayton lived in three different homes—all belonging to men connected to Balboa City School, the private academy Ayton attended—before Andrea moved the family to Phoenix. There he enrolled at Hillcrest Prep, where Weaver served as the basketball coach. “When he first got to us, he was really shy and quiet,” Weaver says. “You could tell he didn’t really trust people.”

Ayton declines to go into detail on these years. Instead, he says, “I’ve been around a lot of snakes, people who say they have your best interest [in mind] but they’re really there for their own purposes. Kids like me, who are in my position, really have to watch out for that. They got guys who will give you their whole world, but they know what you’re going to get in the future and take that away from you.”

I ask how that’s changed him.

“It changed me a lot in how I read people,” Ayton says. “When it comes to my personal life, I watch people around me. Even family members—I watch how they act. Who was there with you with the struggles, especially when all this stuff happened at U of A.”

By “stuff,” Ayton means the ESPN report that came out in February on the heels of the FBI’s investigation into the NCAA. The report claimed Arizona had discussed paying him to come play for the university. It has since been both refuted and denied, though ESPN has stuck behind the story.

Beyond the scope of the world of NCAA infractions, whether Ayton was paid is largely irrelevant—has anyone explained why, exactly, the FBI is essentially conducting an investigation to enforce the NCAA’s corrupt and twisted rule? But what does matter was how the ordeal stripped away Ayton’s adolescence and introduced him to his new normal. And it wasn’t just seeing his name tossed into stories containing phrases like “federal investigation.” It’s the microscope that he’s been thrown under, like the pre-draft scouting reports criticizing his effort and motor while playing at Arizona.

“I don’t get that,” Ayton says, growing animated. “What does that even mean? That gets on my nerves. I honestly hate that.

“I’m playing small ball, switching on guards and then have to go back to the post and switch back onto the guard the whole game. Like, there’s times where they put their best guard at the 4 and I have to guard him all game. I have to run behind screens, come off off-ball screens, then try to rebound, then switch back onto the big.”

That particular critique, he adds, “makes me sick.”

His mother sums it up a few days later over the phone: “His whole season at Arizona, we never got a break. His name was all over the place. He’s such a happy kid, but there I don’t think he ever had a chance to smile.”

Which is perhaps what excites him most about the NBA. Basketball will soon again be fun. In fact, in the time since Ayton’s college season ended and he began his official pre-draft training with Weaver in Phoenix, it already has.

After our interview, Ayton works up a small sweat getting up jumpers with Weaver before heading to the sideline to pack up his things and head home. Two teenage boys approach him. They’re dressed in basketball clothes and have spent the past half hour or so shooting around on a separate hoop. They tell Ayton they saw a Snapchat video he posted earlier during the shoot and recognized the gym’s logo and so they decided to come meet him.

They ask him for pictures and autographs.

Smiling, Ayton fulfills their requests.

—

Yaron Weitzman is a writer living in New York. Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.

Photos by @matthewcoughlin, action shot via Getty Images

Video by Jakob Owens